“We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect… That land is a community is the basic concept of ecology, but that land is to be loved and respected is an extension of ethics.” - Aldo Leopold

Even the most committed naturalists and land conservationists generally don’t begin life attuned to Aldo Leopold’s land ethic. Environmentalists evolve from a perspective of land ownership to land stewardship. This evolution is usually not an epiphany; rather, many unconnected moments transform the human mind over time.

As a child, growing up in rural Connecticut, where the natural world was my playground, land ownership represented a personal challenge to me. Land was owned by other people; every boundary line was an imaginary fence to conquer.

In my twenties, I purchased my first piece of land. I remember driving to the property after the closing, walking to the highest point, and feeling triumphant. I owned this land! The laws of our community gave me rights to build things and tell others that my boundary line was now their fence. My mind raced to envision the property as a house site. It was wonderful! I built a house and raised a family there.

In my forties, I purchased more land, hundreds of acres. I loved the land and wanted to put together a big, beautiful undeveloped property for me and my family. But what began as an enterprise of acquisition changed. I grew more concerned about future generations. As I researched how to manage my land intelligently, I learned about the environmental impacts of my decisions.

One of the moments that reshaped my thinking happened on the day in 2006 when David Strayer, a freshwater ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, NY, invited me to wade with him into the Ten Mile River, which runs through our farm. He had me pick up one of the mussels that lie in the riverbed, and informed me that, while they appeared healthy and abundant, these freshwater pearly mussels were actually the most imperiled group of plants or animals on the continent, with dozens of species already extinct. He told me that every mussel I could find in the river was at least fifty years old because for the past half century some pernicious combination of environmental factors had thwarted their propagation. If no one could figure out what was causing their breeding to fail and fix the problem, the clock would run out on mussels in the Ten Mile River. There was an entire world that existed on our property that I had never seen.

In my fifties, my view of land grew even less anthropocentric when I became a falconer and learned to become a partner with my hawk to assist her hunting. The hawk does not regard land as property lines or zoning regulations; she experiences movement, opportunity, calculation, limitations, danger, initiative, and ultimately survival for her or her prey. The raptor’s-eye-view that I have shared with her has enabled me to partake in the relationship with the land that Aldo Leopold advocated, becoming part of the natural community rather than its owner. I no longer felt the desire to own hundreds of acres; just one simple piece. I began to divest myself of land. I was ready to focus on one special property on the Hudson River...

The Oak Hill Road Property

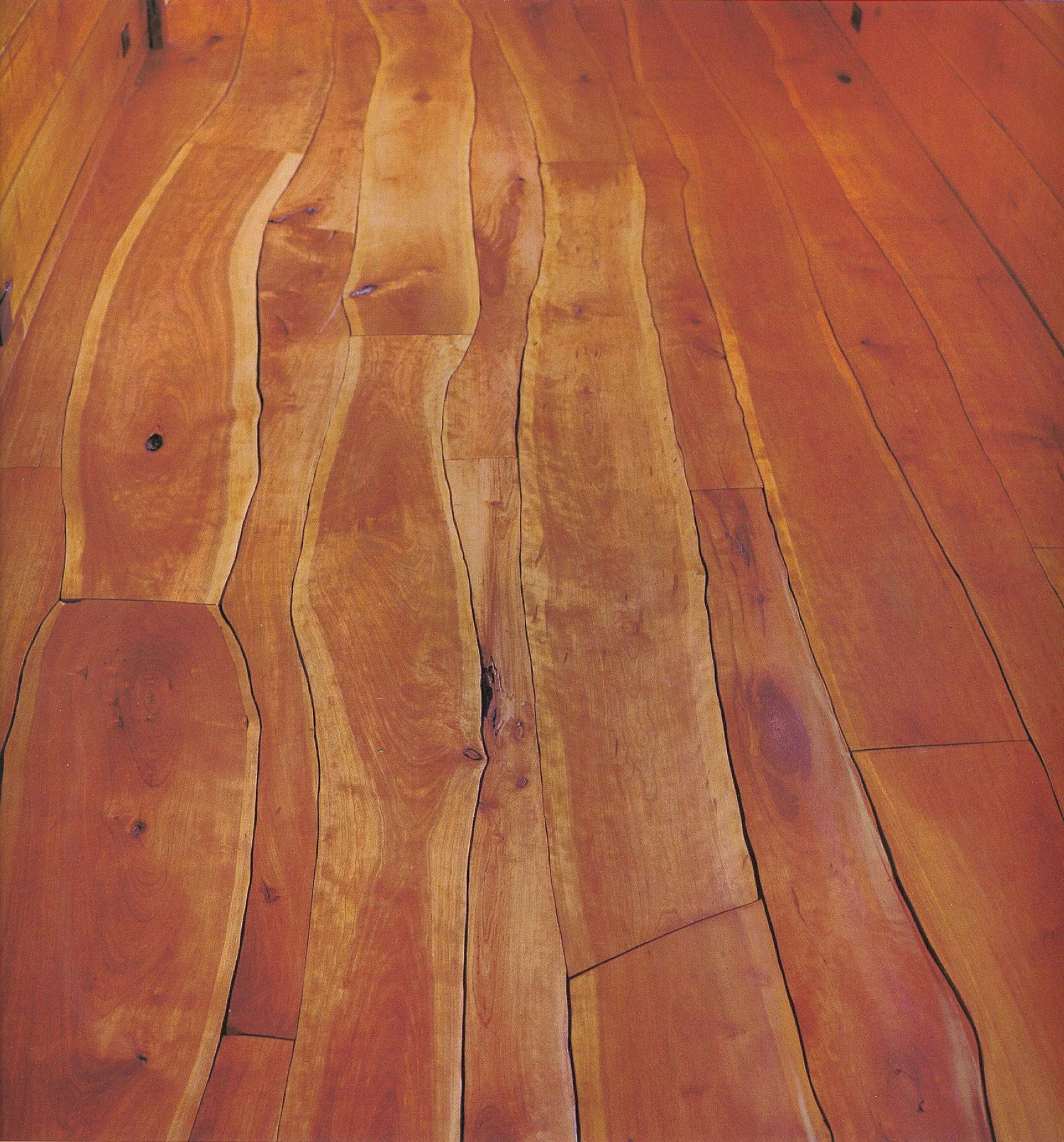

We are about to begin the construction of a new house on Oak Hill Road in Livingston, NY. The site is a high bluff looking south along the Hudson River, with a big view of the Catskill Mountains to the west. While actual construction will begin during the summer of 2013, we have been making preparations for several years: collecting materials from the forest, such as enormous granite monoliths; cutting and drying 80 black walnut trees; building millwork and furniture for the house; creating architectural designs; and doing general site work to install utilities.

My goal is to build a house and develop the property on Oak Hill Road in a way that not only provides for our needs, but also respects and responds to the land and its surroundings, heeding the long-term needs of the environment and society at large. The 3,000-square-foot house will be built into the hillside with a sod roof to shelter us from extreme heat and cold. I have established five design principles to guide me:

The design of the house and landscape should demonstrate a respect for the history of the site and a commitment to land stewardship.

The construction of the house should reflect its time and place through the use of vernacular materials and craftsmanship.

The house should be low maintenance in every respect. We do not want to be owned by our house.

The mechanical systems of the house should be simple, low tech, easy to repair and easy to operate, should use no fossil fuels, and should produce all of the energy required for all domestic hot water and HVAC… a “reduce and produce” approach.

The architecture of the house should demonstrate the power of architecture to contribute to the daily experience.

Whenever I need to make a design decision, I visit the land on Oak Hill Road and let it speak to me. The Hudson River Valley has seduced generations of humanity, and I am no exception. I no longer own the land; the land owns me.